Uncovered Read online

Page 11

I went every Sabbath to the Rakovskys’. During one visit in late spring, Seema told me about Chabad House, the new Hasidic gathering place for Jewish students at the University of Texas at Austin. She spoke about Tuvia, a young pharmacy student there working to build up the place, even neglecting his studies for this holy outreach. Now on Friday nights the new Chabad House filled with Jewish students who came for Sabbath services and free meals.

I remembered my Minnesota friends one long-skirted walk long ago, Sorah, Rus, and Myah, chattering about the Chabad Houses near their colleges that had gathered them in. I wanted friends. “You should transfer to UT,” Seema said. “Go visit and see.” Religious friends, she said, would settle me, anchor me in my faith. Ignore your own rebellious inner voice. That is the voice of a child standing at an abyss. You could fall.

Nine

Click. The driver locked the doors. My cab from LaGuardia Airport had just turned onto Brooklyn’s Eastern Parkway, which forms the border of Bedford-Stuyvesant, at that time a dangerous bombed-out ghetto, and Crown Heights, home of the Lubavitch Hasidic movement. After a semester at the University of Texas at Austin, I had come to the Rebbe on a pilgrimage.

Tuvia had warned me not to cross over into Bed-Stuy, but even on this side of the parkway the street was broken and littered, at least one abandoned building scrawled with enormous black graffiti every block. Lone figures loitered. Shifty eyes. But at the corner of Kingston, I signaled the driver, thanked him, and paid in an eager rush.

Kingston was the main street of the Lubavitch neighborhood, and it was humming with honking cars and hundreds of walking Hasidim. My new family portrait! The shops had signs in both Hebrew and English advertising Jewish ritual items, “Jewish art,” flowers for the Sabbath, kosher pizza, candy, and holy books, and every store displayed a picture of the Rebbe in the window. The men were bearded, boys and men alike clothed in black and white with tzitzis strings at their hips. A few gray-bearded older men even wore the long black Sabbath coat in the middle of the week, like Avram Ayor. The women and girls were all in skirts and long-sleeved dresses under their coats, married women in wigs or headscarves. Many were pregnant, but I ignored that.

Many led small children, boys still young enough to wear bright colors. Mothers pushed strollers with overwrapped, red-faced babies, admonishing children to stay close. Older kids were out on their own, groups of boys or groups of girls. People crossed the street by darting around cars.

There would be no embarrassing stares at my clothes here. I belonged. I was exuberant.

I imagined everyone I saw to be a friend or relative. I imagined the whole busy, moving crowd stopping in place and raising their arms to hold me aloft on that collective strength, those uplifted hands.

I was an immature eighteen. Back at UT, I strode several times a week across the huge campus to Chabad House. There, I washed dishes, cut up salads, set tables for services and other celebrations, and then joined in study sessions, prayer services, and long, noisy Sabbath meals, lustily banging the table along with other girls in closed-mouth rhythm as the boys belted out their songs. During this time I got the message over and over, in Rabbi Frumen’s classes, sermons, Torah talks shared at the Sabbath table, our studies together, comments among my peers at the Chabad House: my real fulfillment would come through marriage to my bashert, the man to whom I was destined. This was God’s reason for my existence.

In spite of all that, I was enjoying school. Under the rigorous eye of a visiting Indian professor who wore white suits and smoked unfiltered Camels in class, I found Keats and Wordsworth, Tennyson and Coleridge. I found a challenging cello professor and began to write poetry. Swathed and sexless, ever conscious of Hasidic demands to subjugate my unholy body, I examined Greek marble nudes in my art history class and learned how the Greeks considered the human body the epitome of spiritual beauty, the perfect form to use to depict the gods. I took Life Drawing again with nude models, tracing curves I longed to touch. My Hasidic parameters now well defined, I moved across the campus solidly inside that glass box, but inside that box I had begun to grow branches and leaves.

And yet I had come to the Rebbe. I wanted it all, the religious spirit and devotion and sense of belonging, and the tiny budding self who loved learning and making music, who wanted to travel the world; I was just a teen full of typical contradictions. I had even written a letter to the Rebbe: “I know I’m commanded to marry,” I wrote, “but I’m not ready. Is it all right if I travel and study first?” Rebbe, I know I should, but I don’t feel, can’t tell, don’t think I want … Rebbe, help me comply and be a good Hasidic girl, and allow me not to comply. Not just yet.

I found the tiny stationery shop where Seema Rakovsky’s father, Rabbi Renner, presided. He had sagging blue-green eyes, a black cloth yarmulka like a bowl on his balding head, suspenders holding up baggy black pants. He welcomed me, then slowly led me around the side of the building to the family entrance, where I was to stay.

The Rebbe’s presence fell like a continual mist over Crown Heights, and that same mist seemed to hang in the Renner living room. The place made me whisper. It was immaculate, with overstuffed furniture, cases of Hebrew books, the Rebbe’s image in a place of honor on the wall. A round table next to a floral chair held at least three dozen framed family photos, all in Hasidic-style clothing, most of them young, including a photo of the Rakovsky children. In the center was a framed miniature of the Rebbe, the whole arrangement a statement of the devoted legions that had sprung from this old couple.

Mrs. Renner, all of four foot eight, welcomed me with a crinkle-eyed smile. “So,” she said. “You have come to the Rebbe.” Seema had told me the whole community constantly opened its homes to people like me. Baalei tshuvah, we were called—newly reconverted searching souls returning to God. Mrs. Renner commanded me in Yiddish to sit at her tiny kitchen table for weak tea and cookies that tasted like sand. I was to stay three weeks, through the break between semesters. She listed when I would have to pray, eat, sleep, and it all came out like grandmotherly fussing and made me laugh. I called her Bubbie Renner. Grandma Renner.

I woke the next morning between starched sheets. I woke to church bells. It was Christmas Day, but on Jewish Kingston Avenue, shops were open, pedestrian traffic unchanged. Outside, I found three different school buses lined up at the curb, each marked in Hebrew letters with the name of a school, all loading children with backpacks and lunches, colorful yarmulkas, tiny sidelocks of hair, tennis shoes. Bearded men streamed out of a corner synagogue, one of several around the community, after morning services.

The shops and shoppers on Kingston seemed a collection of possibilities. Here perhaps I could figure out how to insert myself into this community. I could listen to how people spoke to one another, see what they bought, ate, the books and art and everyday objects they chose for their homes. Each item I examined in their shops built the decor in my imagined house. With the thrill of new membership, I sampled foods, fingered talis prayer shawls and two-handled hand-washing cups, icon photos of the Rebbe, slotted tzedakah charity cans, gilt-edged Hebrew books that opened from the left, and brightly colored children’s books in which the animals were kosher and the children religious Jews learning lessons about God and good behavior.

I rounded the corner of Eastern Parkway and found the massive 770 Eastern Parkway, Lubavitch headquarters, where the Rebbe had his office. There was a subway entrance right there, but it seemed outsiders exiting the subway melted away. Christmas bells tolled at ten and at noon. No one seemed to hear.

Past Lubavitch headquarters, along the border of Bedford-Stuyvesant, happy and confident, I walked at a good clip. I greeted an approaching black teen who looked about my own age with a big Texas hello. In the blur of movement, I did not see his sullen anger and narrowed lids. But just as we drew alongside each other, he spat out, “Jew!” in a deep puh of sound and fired a gob of spit at my feet. It splashed my ankle.

I jumped. Froze, afraid. He glared, lip cu

rled as if a bad taste lingered, as if I were the filth he had just expunged from his mouth.

We looked at each other. I thought he was daring me to say something, but I couldn’t. I had only fear, repulsion, sadness, a paralyzed tongue. I felt I’d somehow fallen onto the wrong side of the divide in his mind. I wanted to say, But you don’t understand.

In that brief face-to-face moment, I wasn’t Leah. And I wasn’t a Hasidic woman, or some soldier of God, or even a secret rebel. I was just a girl with shaking hands who knew that to him I was a hated type with no face. Some soulless invasive species. I thought, There is something very wrong here, and I meant in Crown Heights, but the thought was a weak bubble before it sank. Then it was gone. So was he.

Then I was in front of the crowded plaza that fronted Lubavitch headquarters and led up to the large double-door entry. Hasidim had been pouring into Crown Heights from around the world for days for Yud Shvat, anniversary of the day the Rebbe took on the mantle of leadership. The farbrengen public gathering with the Rebbe would take place that evening. Mrs. Renner had told me that there were always people milling here, local residents, visitors from around the world, even tourists, but with all the visitors in town the crowd was greater now. I tried to shrug off the confrontation with the black teen. I wanted to take in the plaza in the same way I had taken in the scene on Kingston, as a way of embracing this. The bustle and movement had a thrilling, infectious religious busyness to it, an exciting self-importance that said, Vital activities going on here. For God. There were hawkers displaying books of Hasidic philosophy and Jewish law all along the plaza perimeter. They displayed posters of prayers and biblical quotes, key chains and coffee cups and notebooks stamped with the Rebbe’s image, pushka charity cans, mezuzahs, stacks of yarmulkas, tables full of colorful scarves, and storybooks of the Rebbe’s miracles. One teen had a too-large black hat on the back of his head. His friend was chewing gum, black pants low on his hips as if they were jeans. Both had a wisp of dark hair on upper lip and chin. A woman in a shoulder-length wig, heels, and an elegant suit was trying to maneuver a double stroller with two babies in it across the plaza. Two girls in plaid pleated skirts like a school uniform browsed the wares. A dusty man, his coat sleeve torn, put out his palm. There was a bulge in his right pocket. “Tzedukah, hab rachmanus,” he whined. Charity, have mercy. I gave him a dollar. A middle-aged woman held out a can. “Dollars for Beis Rivka,” she repeated in steady rhythm. They wanted to build a new girls’ yeshiva. I pulled out another bill.

Finally, I got across the plaza and stepped through the double doors into the Rebbe’s headquarters. Instantly, I found myself in a place of exclusively masculine gravity and prestige, beards and missions for God. But every Tuesday night, the Rebbe met with both men and women who came as pilgrims. I wanted an appointment with him.

It was a busy place. In addition to the Rebbe’s office and the giant shul auditorium downstairs, the building held a publishing house churning out the Message in six languages, a large yeshiva for ordination, and the Shluchim Office international outreach headquarters for emissaries, all run completely by men. As a female, I was automatically a visitor, an outsider. And every one of the many men coming and going required a protective buffer of space against accidental contact with a woman.

I was hyperaware of constituting a threat and did not venture beyond the lobby. Then the woman with the double stroller came in behind me, holding a brown envelope, and behind her a postman with a large sack of mail. I waited with the postman and the woman. One of her babies was asleep, but the other watched with solemn eyes. I wondered if the letter I had sent the Rebbe the previous week was in the postman’s bag. “Open your heart,” Tuvia had told me. “Tell the Rebbe everything.”

Once, in Denton, I had written a different letter to the Rebbe. In it, I confessed my doubts and waning sense of God, and resistance to Hasidic discipline. I asked his advice. But I was too ashamed to admit I was lacking faith, so, instead of sending it, I taped it into my diary.

Finally a black-hatted man approached with a peppered beard and a hurried “Can I help you?”. He pointed the postman to a narrow office behind him. The woman said something in Yiddish and handed over the envelope. But I felt my still-new status as a woman before this man’s beard, his height, in this building full of men. I said something like, “Oh, I was just looking around.” Then I backed away and slipped out.

Outside, I retreated through a different, unmarked door into the women’s gallery, where I found women gathering before glass windows looking down into the auditorium, where the Rebbe was soon to address the men. In here was the soft, high buzz of quiet mother voices, daughter voices, the squeal of small children, the smells of shampoo and deodorant, hair spray, perfume, mild female sweat, baby formula and spit-up. My eyes adjusted to the dimmer light as I walked in past two unmarried girls, their long, uncovered hair pinned modestly back, sitting side by side and reading a single pamphlet of the Rebbe’s teachings with the rapt attention of yeshiva boys. I wanted to be one of those girls. I wanted their knowledge of Hebrew and Yiddish. I wanted to believe as they did that through that pamphlet the Rebbe was guiding my life, that the world it spelled out was my world. I wanted to belong.

The thick green pane hung down to a wainscoting. The women were mostly stuffed on benches facing the glass, but the best place to watch was a narrow stretch in front of the benches. That space was filled with a crush of bodies. Forget the men assembling below; I tried to make my way in but all I could see was the back of someone’s shoulder. I tried to wiggle farther in but couldn’t make headway. The woman pressing against my left side sighed and stepped out of one of her heels.

“Oh no,” I moaned. “I’ll never get to see.”

“Come back next month,” she said. “The crowd will be smaller.”

“I’ll be gone,” I said.

“Where’re you from?”

“Texas.”

And suddenly she was my personal emissary, tapping the shoulder of the person in front of me. “Let her in. She’s from Texas!” she said. Two different women gave an inch or two. One grumbled, but my new friend persisted. “Let her in!” Then I felt a hand on my arm from somewhere ahead pulling me through and found myself standing near the glass. “Texas?” the girl said. “There’s someone from Texas staying with my grandparents.” It was Seema’s niece.

Up close, I found there was a gap between the scratched green glass and the wainscoting that I could bend down and peer through. I could even get a breath of fresh air.

Below was a huge sea of waving black hats, thousands more pouring into the open hall. I knew they would wait hours if necessary to hear the Rebbe’s complex addresses and join in the singing of their wordless Hasidic hymns. “Hearing the Rebbe is like praying,” I said to the girl who had rescued me.

She nodded and looked at me a little oddly.

Anyone in that crowd would have to claim his inch of space and stay put. At the back were completely filled bleachers all the way up to the very high ceiling. The men on the bleachers were all standing, up to the top row, and all turned to the same side, right shoulders out. I thought of dominoes tipping. “How many are down there?” I said to the girl.

“Mmm. Seven, eight thousand,” she said.

Dabs of color appeared among all that black and white, most on little kids. One boy dropped low and disappeared, then reappeared a few feet away. “Did you see that boy?” I said. “How did he move?”

“They crawl between legs,” the girl said. “Bathroom’s at the back.”

Another dab of color. Pink. “Is that a girl down there?” I said.

“It’s okay until she’s maybe four. I used to go with my father.”

“So that’s her father next to her?”

“Probably.”

There were single orange or green or blue yarmulkas and a few white or brown hats scattered across the sea of black hats. There were baseball caps in many colors, one on a man with a ponytail. These were all clearly

visitors. They were curious, or spiritual seekers, novices like me, or guests invited by those who worked in outreach. But it seemed everyone in Crown Heights worked in outreach, missionaries of the Rebbe never off the job. Girls from the Hasidic high school stuck brochures and packets of Sabbath candles into their purses before they went shopping in the city, in case they met a wayward Jew. Men invited coworkers or strangers on the street. Some went into Manhattan. Are you Jewish? Excuse me, are you Jewish? Most hustled past, but sometimes a Jewish man responded with pride or curiosity and was willing to allow some earnest Hasid to tie tfilin prayer boxes over his arm, wrap the long strap down his arm in the proper pattern, set the headpiece knot at the back of his head, and help him recite the blessing. Perhaps the man remembered his father or grandfather doing the same. The Hasid would share a bit of Rebbe wisdom and invite his potential convert to come here. To the Rebbe.

In the tight crowd below was a long, empty table on an elevated platform, barren island in the sea. There was a microphone set up on the table, and a single chair covered in red velvet. Bleachers behind the platform seemed reserved for the very old; the table stood against a backdrop of long white beards.

Soon began a happy baritone melody that swept over the crowd, filled the room, and rose to the adoring women above. Men bounced in place as they sang. More hats came in. I couldn’t imagine how they would fit in more people. Then, all at once, the singing stopped. A collective intake of breath. Quiet spread like a wave. Fathers lifted children to their shoulders. Behind me, a woman whispered, “He’s here!” and the girl who had pulled me in said, with a tug and a point, “The Rebbe’s here!” I twisted a little more to see, peering down.

Just inside the doors to the hall, standing impassive before thousands of awed waiting men, was the Rebbe: Rabbi Menachem Mendel Shneersohn, Russian born, triumphant escapee from murderous Europe. Our rebbe was a picture of determination and spiritual power, his calm gaze level and deep. He was barrel-chested, with a steel-gray beard that hung to his lapel beneath a black hat large and soft with age. His jacket, knee-length, was belted with a sash.

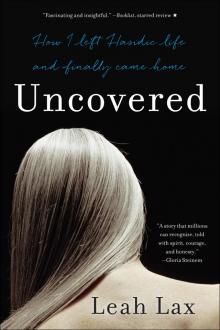

Uncovered

Uncovered