Uncovered Read online

Page 5

“So what do you want?” the rav says.

“Could we use some sort of birth control?” Levi says.

“We don’t do that,” the rav says in a dismissive tone, followed by dismissive silence.

Levi falls dumb into that silence. He doesn’t argue. He doesn’t defend me.

There’s an awkward pause. Heart pounding, I wait for rescue. Then I take a deep breath and make myself speak. My voice sounds unnatural, untried, and every word is laced with the guilt of my immodesty in speaking out. But each word is another step forward through an unfamiliar passage. One day, I will remember this, remember how. “Wait. What if the woman could get hurt?” I say.

“That’s different,” the rabbi says. “But then I would need a letter from a doctor.”

A doctor. My word about my body isn’t enough. “What if ‘the woman’ is physically healthy,” I say, “but she can’t bear the possibility of … of …?”

“Are you talking about psychological harm?” the rav says.

“I guess I am,” I say.

He laughs. “You want permission to break the Law because motherhood is difficult?”

Nobody speaks. The silence is filled with my inadequacy as a wife, as a religious woman, as a potential mother. I am small. Finally, I say, “But I read—we read—that Rav Moshe …”

“Well, then,” the rabbi says, now clearly annoyed, “call Rav Moshe.”

ONE NIGHT TWO MONTHS LATER, I lock the door in the bathroom and position myself in the space between toilet and tub. Behind me, the nylon curtain is wet with droplets from morning showers. We called Rav Moshe the next evening. We weren’t allowed to speak directly to him, but we spoke with his son, his representative, as the great rav sat in judgment nearby. “My father says you will bear Jewish children in joy,” the son said. “You may use a diaphragm for one year from this date.” Now, two months later, I put the top down to the toilet, pull off my scarf, and shake my growing hair back and off my face. Levi is waiting in the other room.

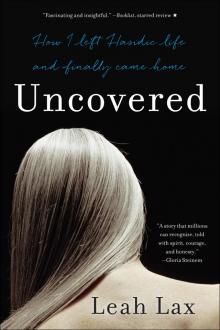

Since we received Rav Moshe’s permission, we have both been finding slivers of freedom, allowing each other that. Levi wears his blue jeans, goes to the symphony, indulges in beloved old movies, even if the Hasidim deem such secular things soulless. I’ve renewed my interest in my university studies. One of my art history professors has offered to mentor me in an independent project about the architecture of Gaudí. I’ve even stopped wearing the wig on campus, and learned intricate decorative ways to arrange scarves. My growing hair now hangs audaciously long and free beneath the scarf.

But at home, even with my partly uncovered hair and his blue jeans, we still have our roles. Levi controls the money, makes the decisions. I’m getting to know him: He has little need for casual touch, and great concern about his obligations outside our home. At times, he surprises me with a gift or a kind word, but in general he’s awkward about my needs, often doesn’t seem aware of them. Our separate roles seem to reinforce his awkwardness, as if, with his position so clearly defined, he has difficulty developing new empathy for mine. That would be crossing a line he doesn’t seem to know how to cross anymore. Perhaps he never did.

But Rav Moshe has given me something. I pick up a yellow plastic case from the counter and take out the thin rubber cup stretched over a rounded spring. I’ve come to enjoy the sploosh of cream into the quivering rubber bowl, the way that I have to pinch and fold the spring in order to lodge it inside me just so against thinly sheathed bone. The diaphragm is teaching me my body’s inner folds and secret chambers, giving me time without babies to learn. I put my right foot on top of the closed toilet lid, left foot on the floor, pull the full skirt up to my thighs. This is Rav Moshe’s gift: a kosher brashness I’m gaining from this new body knowledge.

Now I can cross without consequence the line Levi can’t seem to cross—into his bed. And I do. I approach him for sex again and again. Even though I have little physical desire, I do it anyway, always pleased with his happy response. I do it for connection, and for the aftermath in his arms. Sex seems the only way to get to that warm safe place. The alternative of staying on my side of the Hasidic divide, always near him yet apart, is lonelier than being alone. Besides, I’m trying with everything I have to make sure being in his arms still feels like coming home. Then I test it again, and again, because, more and more, it … doesn’t.

I open the bathroom door and go to him.

Late that night, they begin—transporting dreams that I will not, cannot, acknowledge in the daytime. In my dream, my most passionate, most alluring lover is a woman with black curls and tapered, delicate hands.

Four

Okaaayy!” That was a twentysomething bearded rabbi at the orientation for the Live and Learn Sabbath Experience. He was rubbing his hands together as he addressed the crowd. Dallas’s Shearith Israel synagogue was hosting Lubavitcher Hasidim from Brooklyn, Jews who still lived by the old Code of Jewish Law. The men wore beards and yarmulkas and black and white clothes, while their wives, somewhere in the background, were in long skirts and long sleeves, their hair covered with wigs or scarves. We were among the attendees, Ana and I. It was 1972. I was sixteen, immersed in college plans, intent on moving out to make my mark in the world.

About fifty of us had shown up for the weekend-long program and were sitting in folding chairs at one end of a social hall. I figured, as Ana and I were, most were there like tourists come to see these audaciously different Hasidim in action. We were to sleep over and experience an Orthodox Sabbath, follow all the rules. Which explains why we had come in their costume—that is, in the women’s dress code we were told when we registered: skirt length to the calf, sleeves to midforearm, closed neckline, panty hose. I rarely wore a skirt, preferring jeans or red overalls. But since our families had worked so hard to distance themselves from the “old ways” and blend in, going openly make-believe Orthodox with Ana for the weekend was a heady rebellious game. Anyway, there was also a soaring spirit feeling I wanted out of religion I imagined I could find somewhere, and I believed the Hasidim were all about that spirit. I believed my wannabe family had deprived me of that. Transcendence, Ana called it. A leap above, straight to God.

Ana was two years my senior, and I wanted to follow her, would have followed her, anywhere. We had first met one Sunday two years before when I’d cut Sunday-school class at our liberal Reform temple, where my mother sent my sisters and me each week to sit among the children of her peers and give the impression we were a “normal” family, though at home cockroaches ran up walls, our mother slept through drugged days, and our mentally ill father sat in the living room, grinding his teeth to nubs while reading every word in the newspaper, including the classifieds. I wasn’t interested in the teacher’s do-good theology. I had taken to skipping the classes. That Sunday, I found Ana leading singing kids on guitar, her soprano voice a lovely, lilting vibrato. It didn’t take long for me to attach myself. We were an odd pair, but Ana said I was deep and fearless, and I was simply smitten. She didn’t seem to notice, and yet I’d find her waiting near my school bus in the morning in sunglasses, long brown hair feathered in the wind, the top of her convertible down, radio blaring. She made skipping school an easy decision.

Together we took a different look at Judaism—reading books and experimenting with old rituals our modern synagogue spurned. Others of our friends were affecting a hippie air, or carrying around Quotations from Chairman Mao or The Communist Manifesto, Siddhartha, or Dune, all of us trying on and exchanging identities like costumes in a backstage dressing room. Spending the weekend with the Hasidim was just another supposedly anti-materialist costume to try on, all the more appealing because we did it together. And because our parents hated it. Besides, we had planned to go camping, but it looked like rain.

The youngish rabbi addressing us had long white strings hanging over his belt at either hip that I thought curious. He had a red full beard and he was pale, a large black yarmulke on his balding head. Three others about the same age stood b

ehind him, all in the black and white attire, all apparently feeling a bit on display and mildly self-conscious, arms clasped behind their backs, looking out at the crowd.

“Before we get started,” our rabbi announced, “here are the Sabbath rules.”

Ana grinned. “Game on,” she whispered.

He had a list: The Sabbath begins tonight at sundown and will be over tomorrow night after sundown. Set the lights in your rooms before sundown, and don’t touch the switch. Do not use or touch anything that requires electricity. No writing; no using a car or telephone. Don’t tear anything. No scrubbing or washing—clothing or one’s own body, so better not to brush teeth; no showers; no hot water or soap, but okay to rinse off in cold water if you must.

There were murmurs but little apparent surprise, no laughs or shaking heads. They asked informed questions: Doesn’t Jewish Law allow you to get a child to turn off a light for you on the Sabbath? I’m a doctor, so I can use the telephone for my work, right? It seemed many were well aware of the Sabbath laws. I whispered to Ana, “But I didn’t know any of this stuff.” Still, the people asking questions sounded a little meek before rabbinic authority, as if the rabbi owned the Law. I got that. He owned us for now. Only one question sounded incredulous. “We can’t tear anything, but surely,” the woman said, “you can tear toilet paper?”

We couldn’t. We’d have to prepare that in advance.

I was both leery of these rules and attracted to them. My mother would suddenly decide she had rules she’d never told, her anger at us for not following them a shot out of nowhere. I was always uncertain around her, never getting it right. Love was at stake, bound up with her unknowable rules. In school as well, mysterious unwritten rules made being one of the girls my endless social failing. There I was in overalls, longing for my girlfriend and dreaming at night that I was a boy, watching mystified as other girls pretended to be ‘women,’ girls who didn’t seem themselves anymore as they touched up their makeup and swished around boys.

The rabbi said, “In a few minutes, the women are going to light Sabbath candles. Our women inaugurate the holy Sabbath.”

Our women. The phrase swept me solidly into the group, a reassuring sense of belonging. But it also confirmed that these strangers now owned us. I was confused, conflicted. Our women. “Oh, and one more thing,” the rabbi said. He glanced sideways and swallowed. “Throughout the Sabbath, women and men will participate separately.”

I looked up.

“This is modest,” he said. “Separate is Godly.”

For the rest of this timeless Sabbath, women were to sit apart from the men at meals and behind a partition at prayers. We women would gather separately, pray apart, in low voices, eat apart. At home my mother was cheering the budding feminist movement, Bella Abzug in Congress in her red hats, the Equal Rights Amendment making its slow progress state to state, women burning bras on television. Ana and I had stepped into a different reality.

I supposed this divide no stranger than the other new rules. I decided to treat it like summer-camp orientation, reasonable enough that we would be subdivided into groups with different activities. Anyway, I had just been deemed a woman and thus an adult.

The rabbi went on about how noble, devoted Jewish women have been doing the candle ritual Friday nights for thousands of years. Images of a simple, simultaneous act worldwide played in my mind: little flames at sundown, flickering shadows on walls on every continent, covered heads bowed over centuries. That was real belonging—global, historical. The rabbi said that we women brought light to the world. He paused for effect, gave us a long gaze, then raised his voice. “Now it is time,” he said, “for our women to inaugurate the holy Sabbath.”

He gestured toward a long table at the other end of the hall, covered with unlit candles. He turned and stretched out one arm as if we were honored guests he was ushering into his home. But it also seemed we had no choice.

Around us, women rising, rustle and movement, gathering of pocketbooks, murmurs, click of heels. We had our new mission, to light those candles and create an island in time, a peaceful Sabbath island for our people. And so Ana and I glided off among the women, leaving the men behind. “I feel weird,” I murmured to Ana as we left. I was a Woman now, but this faux, dictated femaleness came from yet another set of rules I couldn’t intuit. Shyness settled over me like a veil.

Perhaps twenty of us gathered around the candle-covered table. “I can do this one. It’s basic Sunday school,” Ana said. She took a book of matches from the pile and lit two of the candles, covered her eyes with her hands, and recited the Hebrew blessing perfectly.

I wondered where all the men had gone.

I also took a matchbook. Struck a match. A sizzle rose, then a blue-and-yellow flame. I was suddenly grateful for this rare sense of belonging. Here we were, all of us immersed in the same moment, the same ritual. Hold the flame to the wick until it burns small and strong on its own. Recite the old words of blessing, hands over eyes. Baruch atah adonoi. I was surrounded by whispers, magnetized to my new companions among wafts of perfume, tiny swaying movements, Ana’s sleeve brushing my arm.

Before me was a horizon of wavering little flames. I may have been planning to leave home and make my mark, but I had also been recently obsessed with the Holocaust, often imagining myself caught in some Gothic horror and sucked into oblivion, and had been nurturing a secret, amorphous fear. In my darker moments, I yearned simply not to become a statistic. Maybe, I thought, maybe we were more than blips in history, more than statistics. Like the rabbi said, we could be women who had just changed the world with the strike of a match. We could mean something. Because, like God, we could create a day.

WHEN I WAS SMALL, I was afraid of the dark. One night, I woke up terrified in the black night. I wanted my mother. Out of bed, I waved jerking, trembling hands for obstacles and found my way into the hall. All along the wall, I knew, were my mother’s huge canvases—we lived in narrowed, cluttered spaces edged in her tilting planes of color, although in the dark, colors were only memory. Curling my toes, I groped past my sisters’ rooms. A lurch, then a halt, fingertips along the stippled wall.

The wall ended at my parents’ doorway. Without that guide I was in a void, breathing hard. I dropped to my knees and crawled like a blind infant; particles in the musty carpet pressed into palms. At the end of this longest journey, I met the drape of my mother’s bedcover. I stood, and became a toddler cruising sideways, inch by inch, around her bed.

I expected my mother to send me back to my room, but she muttered and moved over—no open arms or caress, but I could stay. I slept and dreamed then, but even though I had gotten myself where I wanted to be, the boy I was in my dream was still looking for his mother. In the morning, I woke with need for her a sharp place in my throat. I suppose I have always been compelled to set out clueless through the dark for new places while at the same time looking for safety, ever heading away yet hoping that in the end I will find I’ve come home.

LATER, WE RETURNED TO THE SOCIAL HALL, where they had set up more chairs in two sections with a partition down the middle, for the Sabbath services. The women were to sit on the left.

A second rabbi introduced himself as Rabbi Geller, in charge of the weekend. He was a short, dark-haired man who bounced as he spoke. He positioned himself squarely in front of the men. Soon the men were reciting Hebrew prayers out loud and very fast, not at all together, sometimes breaking out into joyous, deep-voiced song.

The cacophony fell over us like startling rain. I knew enough of the Hebrew alphabet to know that one can sound out the words without understanding, but I was still surprised so many of the men could read. “Wow,” I whispered to Ana. “They are really going fast.”

“You think anyone understands what they’re saying?” Ana said.

“At that speed I wouldn’t even understand English,” I said.

A few of the women read from their prayer books. The rest of us sat quietly and waited for the service to end.

We were not to raise our voices in prayer with the men.

I was restless. I set my gaze on two Hasidic women in the row in front of us, both in wigs and modest clothing. One was older, in a blond nylon wig. The other held a sleepy, thumb-sucking toddler. It seemed as if they were in a play, in costumes for their roles as Women. Both sat up with self-conscious propriety and whispered their prayers. Around us, whistling streams of air from more female-whispered prayers were audible in tiny moments between the men’s songs.

I was bored, feeling like an outsider. I shifted in my chair, tugged at my skirt, then got up. Ana was still enjoying the old melodies when I slipped out.

Six months earlier, I had met with Rabbi Goldenberg, rabbi for the youth at Temple EmanuEl, had driven myself there in my mother’s dusty Impala. I had developed an ache in my chest, like a hum. That ache was such a palpable presence that I had decided it must be my soul. And if there really was a soul, there must be a God.

Sally Preisand was all over national news at the time, recently ordained by the Jewish Reform movement and touted as the first woman rabbi. I had seen her on television, proud, confident, smiling, in a prayer shawl that was long and narrow like a priest’s stole on top of her dress—a startling image on a woman then. My mother had no use for religion, no sense of faith that I knew of, but Preisand was a Jewish woman breaking boundaries. “Will you look at that!” she said, and sat up, her face alive. The Sally Preisand sighting somehow joined with the ache in my chest and the image of my mother’s smiling face and gave me a new career idea.

I was waiting for Rabbi Goldenberg on a bench outside his office when an old man with a white beard walked out. My first Hasid sighting. He was in a double-breasted black coat like a suit jacket, except that it hung to his knees, along with a black hat indoors, and he had white earlocks tucked behind his ears. He passed right in front of scruffy me—close enough to catch his gentle, careworn face, large gray eyes with deep bags.

Uncovered

Uncovered